A CFD, or contract for difference, is a kind of bet on how the price of something will move—without owning the thing itself. You’re not buying shares or gold or oil; you’re guessing whether the price will go up or down. If you’re right, you make money. If you’re wrong, you lose. It’s that simple.

In classic investing, you own the underlying share. You actually hold a piece of the company, which entitles you to dividends, voting rights, and long-term growth in value. In CFD trading, by contrast, you never own the asset itself—you’re only speculating on its price movement.

When you buy real shares through a broker, you can hold them indefinitely, collect income, and wait out volatility; when you trade CFDs, your position exists only as a contract and can disappear the moment your margin runs out.

Over the years, this market has exploded. Millions of people open CFD accounts hoping to turn small deposits into real money. Most fail. Around 70 to 85 percent of retail CFD traders lose money each year, according to data from the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority and brokers like IG.

So if almost everyone loses, it’s worth asking: who’s actually making money from CFD trading?

How CFD trading actually works

A CFD lets you control a large position with a small deposit called margin. Suppose a stock trades at £100, and you want to open a position worth £10,000.

If your broker requires a 10% margin, you only need £1,000 to open the trade (£10,000 x 0.10). The broker effectively lends you the other £9,000.

Apps like IG, eToro, Plus500, and CMC Markets make this process feel effortless. You swipe, click, and you’re suddenly controlling ten times your capital.

But that leverage cuts both ways. If the stock rises 10%, your £10,000 exposure earns £1,000. You’ve doubled your £1,000 margin. But if the stock falls 10%, you lose that £1,000.

In both cases, you never owned the stock—only a mirrored contract tracking its price. Meanwhile, costs quietly accumulate in the background.

CFD trading costs: Spread, financing, commissions

The first cost is the spread—the gap between buying and selling prices. If the asset is quoted at £100, your broker might sell to you at £100.20 and buy back at £99.80.

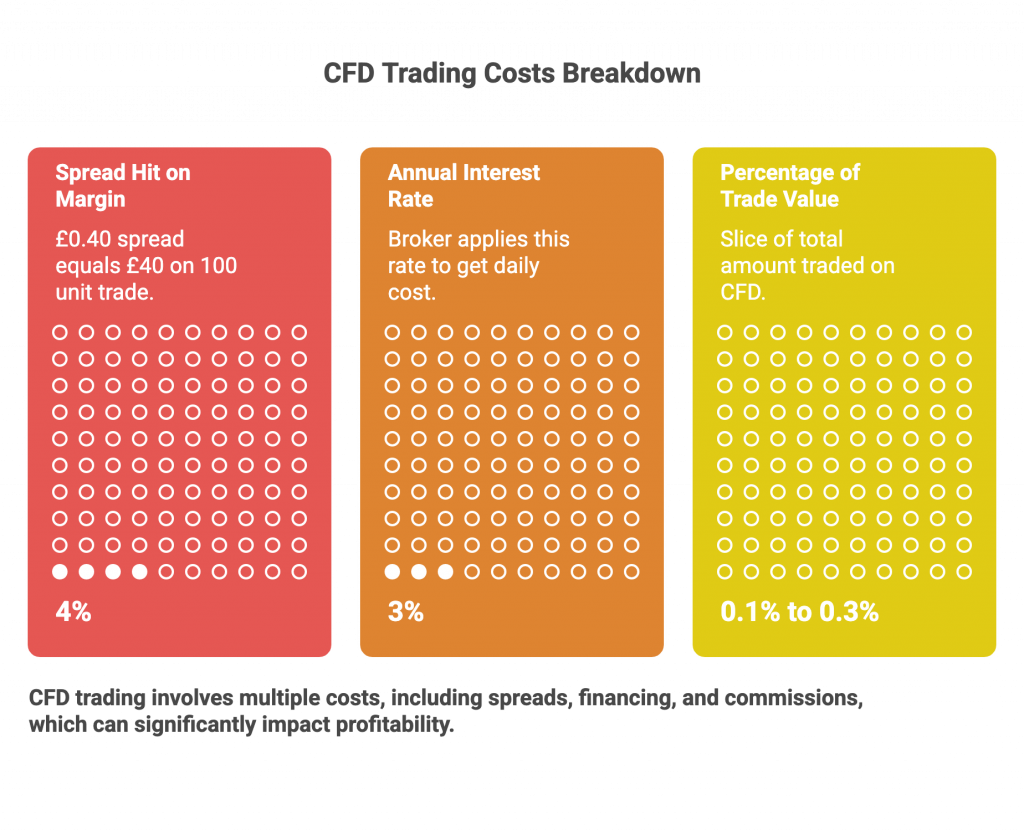

That £0.40 spread equals £40 on a 100‑unit trade, an instant 4% hit on your £1,000 margin. Spreads vary by asset and liquidity, but they always favor the house.

Then comes financing. If you keep the position overnight, the broker charges interest on the borrowed £9,000. Here’s how it works:

- Daily interest charge – The broker applies an annual rate, say 3%, and divides it by 365 to get the daily cost. On £9,000, that’s about £0.74 per night.

- Long vs. short positions – When you’re long (buying), you usually pay interest. When you’re short (selling), you might receive a small credit if market rates allow—but most brokers still keep a portion.

- Weekend and holiday adjustments – Holding trades over weekends can cost three days’ worth of interest at once, since markets close but your borrowed funds remain active.

- Variable rates – Some brokers tie financing to benchmark rates like SONIA or SOFR plus a markup, so your rate can rise when central banks hike interest rates.

It sounds minor, just a few pounds per night, but over weeks or months it compounds fast. A £0.74 nightly charge becomes £22 over a month of holding. That constant drip erodes profits quietly, turning what looks like a small cost into a steady drain on your margin.

Commissions are the extra fees you pay each time you open or close a trade. Here’s how they work:

- Flat per-trade fee – Some brokers charge a fixed rate, like £3 per transaction, no matter the trade size. This is common with brokers like Saxo and Interactive Brokers.

- Percentage of trade value – Others take a small slice of the total amount traded, say 0.1% to 0.3%. On a £10,000 CFD trade, that’s £10–£30 each time you enter or exit.

- Minimum fees – Many brokers apply a minimum commission (often £1–£3) to smaller trades so they still earn a margin.

These layers stack up quickly. Even before price moves, you’ve paid spreads, maybe a commission, and soon a bit of overnight interest. For you to profit, the market must first climb enough to cover all those costs. For the broker, it doesn’t matter which way the price moves—they collect regardless. That’s how the system stays profitable long after most traders exit.

Why most traders lose in CFD trading

The odds are brutal. The FCA says roughly 80% of CFD traders lose money. Research from Quantified Strategies puts the loss range between 62% and 82%, depending on the broker. Back in 2011, a Berkeley study on day traders found that less than 1% consistently make money over time—and most of their profits don’t survive costs.

Why is this? The reason goes beyond math. Consider how the structure of CFD trading mimics a casino. Every trade costs you a small percentage before you even begin, much like the house edge in roulette or blackjack. Over time, those small disadvantages compound into certainty for the house and near-guaranteed losses for you.

Leverage is like playing multiple tables at once—it feels exciting but multiplies your exposure. Traders who win early often increase their stake size until one bad move wipes them out. The system punishes even a small mistake.

And psychologically, we’re wired for it. We crave the dopamine rush of a win, so we chase it. We double down after losses because of something behavioral economists call loss aversion—we hate losing more than we like winning. Add overnight financing fees and a few losing streaks, and even disciplined traders find their accounts thinning.

Like casinos, the entire setup ensures consistent returns for the house. The more you play, the more certain the outcome becomes. A few gamblers might walk away rich, but the structure guarantees the casino keeps the lights on—and in CFD trading, the broker always keeps the lights on.

So, who actually wins in CFD trading?

The real money sits in the ecosystem that surrounds the trader. Every player attached to this industry earns differently, but their earnings share one thing in common: they don’t depend on whether you win or lose. These are:

- Brokers

- Educators

- Platforms

- Affiliates

- Regulators

Let’s start with the broker. A broker collects spreads and overnight fees from thousands of small accounts every single day. Even if each trader loses just a few pounds, those add up across tens of thousands of trades. The broker wins by volume, not by prediction.

Then there are the educators—people who sell the dream of financial independence through trading courses, signal groups, or mentorships. Many of them make more from selling the method than using it. If you’ve ever seen an ad saying, “I turned £500 into £50,000,” you’ve seen the marketing arm of this ecosystem at work. Their customers aren’t brokers, but hopeful traders buying belief.

Data platforms and tool providers come next. Platforms that offer live charts, analytics, and backtesting software charge recurring subscriptions. Whether the market goes up or down, traders still need their dashboards, alerts, and price feeds. It’s a nice, dependable business—like selling weather reports to sailors.

Affiliates are another layer. They don’t trade either, but send traffic. A YouTuber or website owner refers new traders to a platform and earns £100–£1,000 per signup. Multiply that by a few dozen signups a month, and you’ve got a tidy income stream with zero market exposure.

And above them all sit the regulators and governments. They issue licenses, collect annual fees, and tax the winners. The system stays alive because everyone surrounding it profits from activity, not performance.

In short, the people who truly win in CFD trading aren’t the ones placing trades. They’re the ones building, maintaining, and monetizing the environment that makes trading possible.

| Winner | How they profit |

| Brokers/platforms | Earn spreads, financing, and commissions no matter the outcome |

| Course sellers | Sell signals, mentorships, and “trading systems” to new traders |

| Data providers | Charge subscription fees for charts, news, and analytics |

| Affiliates | Get paid to bring in new traders |

| Regulators and governments | Collect taxes and licensing fees |

These players make steady, predictable income because their revenue doesn’t depend on your performance. They profit from activity itself, not success.

Should investors get into CFD trading?

It’s tempting to think that with enough discipline or study, you could be part of the lucky minority who win at CFD trading. But when you look at the data and how the system is built, it’s clear that it rewards patience and ownership far more than prediction.

Warren Buffett has said that the stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient. In Berkshire Hathaway’s 2002 annual report (summary here), Buffet described derivatives like CFDs as toxic “time bombs” and lethal “weapons of mass destruction.”

Instead, he buys businesses he understands and waits years, sometimes decades, for them to grow. That’s how compounding works in the real world: slow, boring, and powerful.

Other seasoned investors echo the same caution. Jack Bogle, founder of Vanguard, warned that short-term trading is “a loser’s game” because costs and emotions eat away returns. Charlie Munger once said, “The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting.”

Even George Soros, one of the most famous speculators in history, admitted that surviving in markets requires humility and risk control.

For most investors, CFDs sit closer to entertainment than investment. You can win a few rounds, maybe even a streak, but the odds and fees grind you down over time. Serious investors focus on ownership—shares, funds, or businesses that build value—rather than bleed their money through spreads and leverage.

The question isn’t whether you can beat the CFD market. It’s whether you want to play a game where the odds, math, and structure are built against you.

Tax implications of CFD trading and spread betting

CFD profits are usually taxable, and that reality often catches new traders off guard. While losses can sometimes offset gains, most tax authorities limit how much can be written off.

In the UK, profits are taxed under capital gains, which means you owe a percentage of your net winnings after deducting any allowable losses or expenses. Spread betting in the UK is considered remote gambling, so profits from spread bets are tax-free.

In South Africa and Nigeria, the closest sources I could find on derivative trading tax implications were related to forex trading. In both countries, the taxman treats CFD profits as taxable income.

Elsewhere, the rules vary. In Australia and most of Europe, CFD gains are taxable income. In the US, retail CFDs aren’t offered widely.

Wherever you are, the bottom line is simple: governments may warn about the dangers of CFD trading, but they’ll still take their share when you beat the odds. Like brokers, they profit from participation, not success.

Why does CFD trading exist at all?

If it’s so destructive to retail wealth, why does it exist? Because the ecosystem is enormously profitable for everyone except the average trader. Brokers make steady margins on every transaction. Governments collect taxes and fees. Regulators justify their oversight budgets. And traders get an emotional payoff—the sense of control and participation in something thrilling and high-stakes.

It’s a perfect marriage of capitalism and psychology: a product that feels like opportunity but functions as entertainment.

CFD trading also survives because it fills certain gaps. It gives people who can’t afford big capital outlays access to global markets. It offers instant action, liquidity, and leverage, all from a phone screen. In an age where people want speed and control, it delivers both—even if that control is mostly illusion.

There are also legitimate uses. Large institutions sometimes use CFDs to hedge currency or equity exposure quickly, without having to move or disclose their positions publicly. Some professional traders use them for short-term arbitrage or risk-balancing strategies. But these are minority cases involving expertise, capital, and tight risk controls.

For the average person, CFDs remain what they’ve always been: a fast, fee-heavy, adrenaline-fueled game that looks like finance but behaves like gambling in a suit.

How to actually win in CFD trading

If you want to benefit from the CFD trading world without becoming its product, you have to think like the people who run it. Instead of betting on markets, build or support the tools that traders can’t live without.

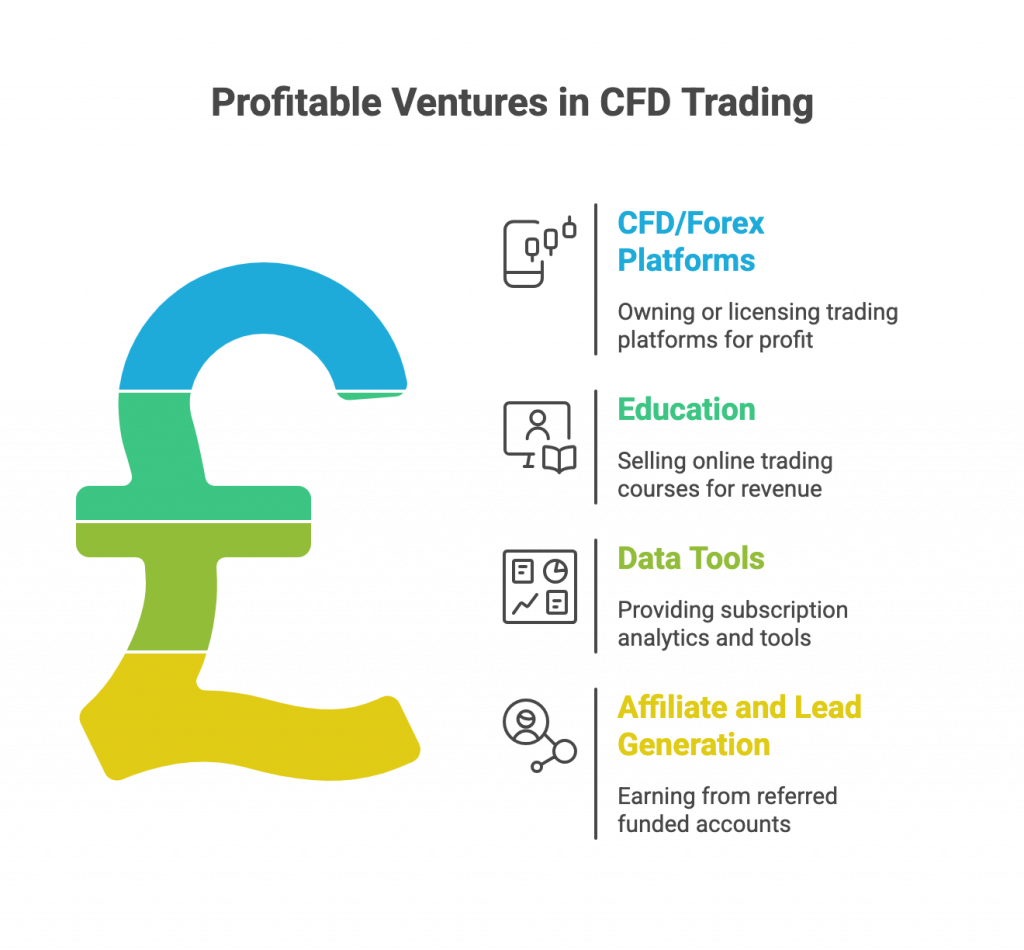

For example, owning or licensing a CFD or forex platform can be extremely profitable. A full MetaTrader 4 license historically cost around $100,000 upfront, plus about $10,000 monthly for server and maintenance costs, according to Trading View. Brokers using white‑label versions pay a bit more and still earn consistent revenue from spreads and financing fees.

Another play is selling education or data tools. A single online trading course can sell for £200–£1,000 per student. Subscription analytics like TradingView or TrendSpider charge $15–$60 per month to hundreds of thousands of users. Developers who build bots, charting systems, or risk calculators can license their products to brokers or retail traders for recurring revenue. These businesses scale with engagement, not luck.

Affiliate and lead‑generation operations are just as lucrative. As we saw earlier, brokers pay anywhere from $100 to $1,000+ per funded account referred. That means a content site, YouTube channel, or Telegram group that brings in 100 new signups a month can make a reliable five‑figure income without placing a single trade.

In all these models, you profit from the activity, not from calling the market right. It’s the difference between owning the casino and sitting at the table. The real money isn’t in guessing the next tick, but in building the systems that let everyone else try.

Final thoughts

CFD trading looks like a shortcut to financial freedom. In reality, it’s a system designed to extract small amounts of wealth from many participants and funnel it upward to a few infrastructure players. It survives because it feels like opportunity even when it isn’t.

So if the odds are 80% against you, the question isn’t whether you can beat the system. It’s whether you even want to play the game in the first place.